By Emily Hoover

Little did I know when I first walked through the doors of Alderman Hall that I would subsequently spend my academic career in this building. It was March 1977 and, intrigued about the prospect of graduate school, I ran into Mark Brenner by chance in the hallway. He would become my MS and PhD advisor—and, once I was hired as faculty in the same department, my colleague. But now I am bidding farewell to Alderman Hall and a career I have loved. I’ve been an educator and professor for 41 years but also a learner. Many of the lessons I have assimilated into my life have been from students, the grower community and from all of you. As I exit my formal role in the Department of Horticultural Science, here are a few lessons that I hope can be useful to the next generation.

First, I learned that teaching is about aligning course content with student goals. When asked what I liked about being a faculty member, I have always said working with students. Recently I found my essay for graduate school, and it’s clear from rereading it that even then I was inspired to teach. Education is such a wonderful back-and-forth between people, teaching and learning, the yin and yang of each other. During my career, I have always tried to start with students. This seemingly simple commitment is surprisingly difficult to apply consistently in practice. As a new teacher, I naturally assumed my own perspective, often starting with the content or the method rather than what my students might want or need. For example, I began teaching a course on fruit crop production early in my career. I remember distinctly when a student turned in his midterm early during the exam period having left some of it blank. When I asked whether he wanted to do more of the exam he replied, “I did enough for a “C” and that is all I need.” I also remember that as an overachiever, this statement stunned me. He went on to have a productive career in the horticulture industry taking on a number of leadership roles. But this incident taught me an invaluable lesson: that students’ goals are entirely their own, and it was my role to understand and support them.

To do so, I learned that building relationships across your community leads to better outcomes in class and unexpected impacts beyond the classroom. I realized over time that to transmit my enthusiasm for science and plants in ways that would resonate with our community of scholars, I would need to understand who they were, where they were and why they were at the University, individually and collectively. For instance, I taught General Biology with class sizes around 300 students. When I first started teaching this course, I felt like a performer. There was a glass wall between the students and me. It took courage for students to “break” the wall to come up and ask questions. This bothered me and so I joined a UMN program called “take students to lunch”. Each week I would have 10 students from this course come together and talk about what was going well and what needed to change. These conversations were eye-opening for me, as the students told me that they were committed to learning biology, but did not see as much connection as they needed between lecture material and exam questions.

This is when another “aha” moment occurred. I would not have used the same testing method with smaller classes, yet I had for this large class. I still had the same goals for them to understand the content and be able to use it appropriately. I re-energized how material was presented in my in-class sessions: in small groups (with overhead plastic sheets and a marker) we would tussle with a given question. I would randomly point into the auditorium and ask the group to come up and explain their answer. It took audacity for those first groups to speak up and engage, but over time it proved very effective; I was proud when my sections surpassed others in performance on exams. Learning why my students were taking that course, mostly as a prerequisite for others, invigorated my teaching. Years after I stopped teaching General Biology, a student emailed to tell me that I had been a role model for her and convinced her that she could excel in biology. The email was sent the day she graduated from medical school. I take great pride in the teaching awards that I have received over my career, but it’s these kinds of personal interactions motivated by genuine affection that most affirm the meaningful impacts I’ve made in students’ lives and they’ve made in mine—impacts that nobody can predict on the first day of class. The awards are but a testament to the students I was privileged to educate and the colleagues who believed in me as an educator.

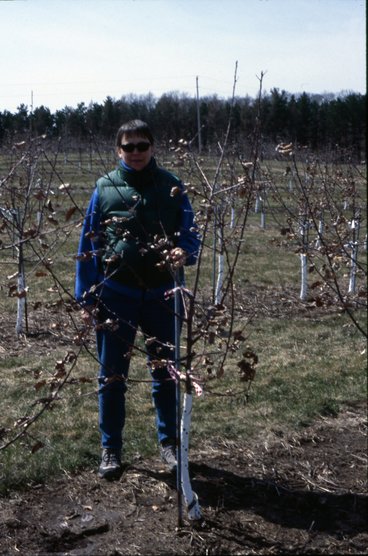

Mentorship is important in all of our lives. As a new faculty member, I joined the regional research group, NC140, with the goal to test rootstocks for temperate fruit species under varying environmental conditions across the US and Canada. Minnesota has the harshest climate—the lowest winter temperatures. This community of scholars welcomed me; they invited me to give presentations at international conferences as the “newbie.” This mentorship was vital for me as a developing scholar. Since 1982 UMN has participated in 10 apple rootstock plantings, each lasting for 8 to 10 years. One of the plantings was located in Lake City at Pepin Heights Orchard. The lessons I learned from the growers and what I have shared with them, again, weave into mentoring and educating among members of a community—the fruit growing community. There is one last NC140 planting with one more year of data collection for 2023. As this planting concludes, I will celebrate the outstanding researchers and growers that welcomed me and set me on my research pathway.

But research would not be possible without committed graduate students. I have had the joy and privilege of working with so many talented students. They have brought intellectual energy into my research programs, as well as great insights. All that I have written about listening to students, understanding their goals, and helping them achieve those goals is what I hope I also brought to graduate students who have worked with me across my career.

This brings me to the final lesson I’ve learned, which is the value of community in supporting an individual career, and vice versa. My own strength as both a researcher and teacher is a reflection of the strength of my community of wonderful colleagues. I could have spent more time in this essay listing my research and professional accomplishments. But that really is not what I want to convey. And in truth, those accomplishments would not have been possible without the countless conversations I had with each of you, the research ideas and collaborations we built together, the teaching suggestions and consultations we shared, the nominations you generously made on my behalf, the list goes on. I want my colleagues to know how very grateful I am for their support in highlighting my work. I hope that I have given them as much as they have surely given me. The department is like one big family. We have spent decades with each other—not always agreeing, but being respectful and supportive of each other. I will miss the intellectual conversations (as well as kvetching about the latest issue on campus), chance conversations in the hallway or meeting new members of the department waiting for the microwave in the kitchen. I will miss working with such talented individuals across the University of Minnesota to accomplish the mission of our wonderful institution.

As I move on to the next chapter of my life, I will continue to be a learner and bring these lessons with me. I cherish the time I have spent with the many generations of students, faculty, and staff in Alderman Hall in the Department of Horticultural Science and celebrate having been a member of the University of Minnesota community. I look forward to the bright future ahead.

In 2019, Dr. Emily Hoover started the Learning Garden Fund. Help the legacy of the Learning Garden grow by donating today!